Conversion therapy, the harmful practice of trying to change someone’s sexual orientation or gender identity is still legal in the UK – but it’s not the only way the LGBT community, especially women and trans people, still face discrimination in accessing healthcare. Courtney Welu reports

When I first had the idea for an article about discrimination against the LGBT community in healthcare, the first responses I got were, ‘that doesn’t happen here.’

However, a new study from the American Heart Association shows that people who identify as transgender are more likely to suffer from cardiovascular disease. Trans men are four times likelier than cisgender men to have CVD, and trans women are two times likelier than cisgender women.

While the causation of this is not entirely known as this is the first study with a large sample size focused specifically on CVD, it’s likely that this difference in health is a result of a combination of an increase of social stressors and stress as a result of neglect, abuse, and mistreatment of transgender people.

Yet almost no health research goes into understanding these health concerns that specifically affect the transgender population.

This holds true not just for transgender people, but also all LGBT people accessing healthcare. There are both explicit and implicit biases in our healthcare system against LGBT people that haven’t been addressed properly in our healthcare system, the worst of which is conversion therapy.

As Channel 4 News reported in February, there is startling information about conversion therapy’s destructive nature.

More than half of those who undergo conversion therapy – the psychological practice of trying to change someone’s sexual orientation or gender identity – report mental health issues afterwards, and nearly a third attempted suicide, according to Channel 4’s report. The effect of conversion therapy is not a changed sexuality or gender identity, but severe psychological damage.

According to the report, hundreds of people in the UK have undergone conversion therapy, and religious leaders were instrumental in forcing them through the process. Over half of victims were under 18.

The horrific legacy of conversion therapy

David Matheson, an American ex-gay conversion therapist, recently came out as gay himself and disavowed the practice of conversion therapy, claiming that the system that perpetuates the idea of a ‘gay cure’ is horrifying and should be banned.

There are plenty of reasons that someone might believe that discrimination against LGBT people isn’t pervasive anymore. LGBT people are more visible than in years past, same-sex marriage is legal, and other laws and policies across the world have improved the quality of life for the LGBT community.

Not being aware that inequalities still exist is a product of privilege, however. Privilege stops people from realising the extent of problems that still exist. If you never have to think about doctors forcing you into conversion therapy, why would you? It doesn’t affect your life, it might not even affect anyone you know.

That doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen. Even if you live in a large, seemingly open-minded city.

The new film Boy Erased is about a young boy raised in the Baptist church who is forced by his parents into conversion therapy. The film shows the horrific violence in conversion therapy, but the Guardian‘s Eva Wiseman reminds us in her article about the film that violence is not the only ‘erasing’ of LGBT people.

It’s more than just graphic beatings and abuse; it’s the assumption of heterosexuality in any and all aspects of life, and the silence and assimilation is just as harmful to the quality of life for LGBT people all over the world.

We all live in a society that promotes heterosexuality as the unquestioned norm.

More than half of people who undergo conversion therapy report mental health issues afterwards, and nearly a third attempted suicide

The reality is that discrimination can happen anywhere, at any time, regardless of where you live. Homophobia and transphobia are still powerful, toxic forces in the world whether you have to think about that every day or not.

We talk a lot about the medical field not understanding women’s needs in healthcare but imagine how much more difficult healthcare is to navigate for LGBT women when almost all women’s resources implicitly or explicitly assume heterosexuality as the default.

In healthcare, discrimination and unequal treatment are particularly harmful. If you can’t access quality healthcare resources and feel safe with your doctors and nurses, how are you supposed to live a healthy life?

Even in Britain, glaring healthcare inequalities for LGBT people

In 2017, Stonewall UK conducted a survey of LGBT people about their life in Britain today, specifically regarding healthcare.

Stonewall is an LGBT activism organisation that advocates for LGBT people in all areas of life, whether that be helping create inclusive work environments, safe schools, or any number of issues.

The LGBT in Britain Health Report shows glaring issues that LGBT people still face in accessing healthcare. Discrimination, hostility, and unfair treatment from medical professionals prevent the LGBT community from receiving equal treatment.

One in eight LGBT people – 13 percent – have experienced some form of unequal treatment from healthcare staff because of their sexuality or gender identity, the report found.

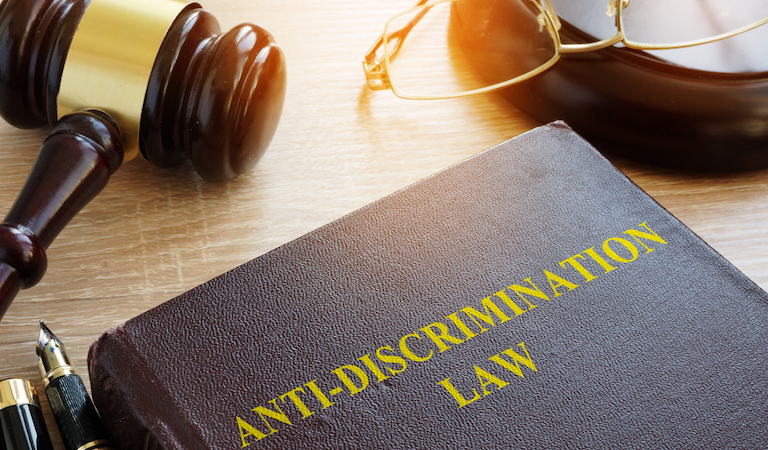

‘Healthcare services have a legal duty under the Equality Act 2010 to treat LGBT people fairly and without discrimination,’ the report states. ‘However, this research shows that LGBT people continue to face these barriers in accessing healthcare treatment today.’

‘The Equality Act fundamentally protects people on the basis of being or being perceived as LGBT,’ Laura Russell, head of policy at Stonewall UK, says. ‘That should apply in a healthcare setting as well.’

In the US, there isn’t equivalent federal legislation to the Equality Act that protects LGBT people. There are, however, various state laws that protect their LGBT populations but some states do not have protection for their LGBT communities.

However, regardless of where you’re from, existing laws and policies aren’t enough to stop discrimination – particularly on an individual level.

‘Until very recently, I seldom had a good relationship with health centre staff, GPs and nurses,’ says one of the survey’s respondents, Linda, 65, from Scotland. ‘It seems to me that it never occurs to many of them to ask for or be receptive to information about gender and sexuality so that they can factor this in when dealing with healthcare needs. I suggest much better training is required in some areas. I’m 65 now and this is a concern as I think about as I age and how people are treated in hospital and care homes.’

Asking about someone’s sexual orientation isn’t discriminatory; it’s how you treat them after they answer where discrimination comes into play. However, being receptive to information about gender and sexuality doesn’t necessarily need to mean outright asking for it.

24 percent of patient-facing staff have heard their co-workers make negative remarks about LGBT people

If a person like Linda is willing to share their sexuality and sees it as important to their treatment, doctors and nurses need to respond appropriately and adjust their treatment if necessary. They need to know how to receive information about gender and sexuality without reacting poorly or defensively.

Regardless of what’s written in the law books, there are still plenty of ways to make LGBT people uncomfortable and perpetrate unhealthy attitudes about gender and sexuality.

Ruth, a nurse from London, reported to Stonewall in their survey on Unhealthy Attitudes, ‘I think that health care professionals sometimes need to be more aware and more sensitive of people’s sexuality, mainly in social terms. They need to be more accepting of same-sex partnerships and their rights as next of kin.’

Healthcare Professionals

Stonewall has done other research in healthcare as well in addition to their LGBT in Britain Health Report. They surveyed medical professionals about what happens at the institutional level when it comes to treatment of their LGBT patients.

Their report from 2015, Unhealthy Attitudes, found that 24 percent of patient-facing staff have heard their co-workers make negative remarks about LGBT people and use discriminatory language. 5 percent of them saw co-workers provide patients with poorer treatment because of their sexuality.

One in ten of the survey respondents said that they don’t feel confident in their ability to meet the needs of LGB patients, the number rising to one in four when it comes to addressing the needs of trans patients.

Another issue with the healthcare system is that according to Stonewall’s report, 57 percent of health and social care practitioners said they don’t consider sexual orientation to be relevant to a person’s health needs.

‘There is a shocking lack of importance placed on awareness of issues surrounding sexual orientation,’ says Jim, a social worker from North East. ‘Racial issues and those from ethnic minorities are seen as important; indeed, information detailing these issues are required as part of the assessment process. However, sexual orientation is often ignored or side-lined as irrelevant to a community care assessment, which I feel results in a lack of knowledge about that person.’

Unhealthy Attitudes points out that ‘whilst on some occasions this may be considered well-meant, it goes against the NHS’s principle of person-centred care. This advocates the value of treating patients and service users as a ‘whole person’, where different aspects of their identify, their families and loved ones, and their individual priorities and goals are all considered relevant in providing the best possible treatment and support.’

In other words, it’s necessary for healthcare professionals to be able to understand the differences in LGBT people’s experiences and needs in order to treat them properly.

‘We’re talking about a whole person, so everything concerning the person is relevant,’ says Ling, a nurse from the South West.

For an example, think about the new study about the correlation between transgender people and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease – if a doctor treats a trans patient in the same way as a cis patient, then there can’t be any forward-moving research into how and why transgender people are at a greater risk for CVD. The issue will keep occurring rather than be researched and understood, and the community will continue to suffer.

However, it’s important to remember that most healthcare professionals are trying their best to provide inclusive treatment. As Laura Russell of Stonewall points out, ‘Quite a lot of healthcare professionals do a lot to include LGBT people, and it’s important that they’re recognized.’

There is an extensive list of health and social care organisations that are members of Stonewall’s Diversity Champions programme that helps educate employers and foster more inclusive LGBT-friendly environments.

There are also healthcare organizations participating in the LGBT Foundation’s Pride in Practice, a service that works with healthcare organisations to help provide the best care possible for LGBT patients and train healthcare professionals.

Healthcare has made many improvements in being more inclusive over time, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t more we can do to help mend the gap and hold the fewer healthcare professionals responsible for homophobic and transphobic treatment in healthcare accountable.

Conversion Therapy

The continued existence and practice of conversion therapy is perhaps the most outwardly homophobic and transphobic aspect in the medical field. The fact that it is still legal in the UK – and practiced – suggests we’re certainly not as advanced in the acceptance of the LGBT community as we might think.

Conversion therapy is the idea that being gay, bi, or trans is an illness that can be treated. It attempts to change or suppress someone else’s sexuality or gender identity and is most often perpetrated by religious institutions.

It’s impossible to change someone’s sexuality or gender identity, and the practice has been condemned by every major counselling and psychotherapy body in the UK, along with NHS England and the British Medical Association.

David Matheson, the gay conversion ‘therapist’ who came out as gay earlier this year, told Channel 4 that the practice does not work, and needs to be stopped because of the immense harm it causes those who undergo it.

Despite the government’s efforts, conversion therapy is still legal in the UK. It’s partially banned in the US, Canada, and Australia, depending on the area.

‘The government is working on ending the practice,’ says Stonewall’s Laura Russell. ‘They’re looking at a broad range of options including policy intervention and potential legislation, but they’re conducting widespread research to try and understand exactly where this practice tends to happen, what these practices are, and the most effective measure that can prevent them.’

According to Stonewall’s LGBT health survey, 5 percent of respondents have been pressured into conversion therapy or the equivalent while trying to access general healthcare. Trans patients are more likely than LGB patients to be recommended to or undergo conversion therapy.

22 percent of London-based medical professionals encountered co-workers expressing the belief that conversion therapy was a viable option

Ezmae, 40, from Wales reported that ‘My ex-girlfriend who had self-harmed tried to look for support and counselling, however she was directed to a Christian counsellor funded by the church, and the general consensus was being gay is making you self-harm so you can be healed by returning straight.’

Stonewall found that medical practitioners working in London were twice as likely as staff across Great Britain to have witnessed their co-workers expressing the belief that conversion therapy was a viable medical option. 22 percent of London-based medical professionals encountered this from their colleagues, more than one in five.

Problems in accessing healthcare

LGBT people often have specific healthcare needs overlooked by medical staff, leading to a lack of trust in their healthcare provider and the healthcare system in general, according to Stonewall’s report.

Shockingly, 40 percent of trans people and 7 percent of LGB people who aren’t trans have reported that they have struggled with accessing healthcare. Almost one in five disabled, black, Asian or other ethnic minorities, and those aged 18-24, have experienced these difficulties.

27 percent of trans people and 20 percent of those who were HIV positive were denied treatment outright

16 percent of trans people and 2 percent of LGB people who aren’t trans have been refused treatment entirely.

The National Women’s Law Centre in the United States found in a similar report from 2014 that 8 percent of LGBT individuals, including 27 percent of trans people and 20 percent of those who were HIV positive were denied treatment outright.

The participants in this study reported harsh language, healthcare professionals refusing to touch them, and being blamed for their health problems.

Refusal to provide healthcare services for LGBT people can lead to extreme consequences. In one case cited by the National Women’s Law Centre, a 39-year-old teacher allegedly died because her medical condition was not taken seriously by the EMTs who became aware she was a lesbian. She was left unattended for over an hour at the hospital, a huge breach of protocol, fell into a coma and died several days later.

Even if there is no outright denial of treatment, that doesn’t mean the treatment is equal.

Stonewall found that 17 percent of lesbians and 8 percent of bi women reported unequal treatment by healthcare staff, with lesbians being the cisgender group that experiences this unequal treatment most.

However, trans and nonbinary people experience this more than LGB individuals: one third of trans people and one fifth of non-binary people reported unequal treatment in receiving healthcare. One in five black, Asian, or other ethnic minority groups have also reported unequal treatment to Stonewall.

17 percent of lesbians and 8 percent of bi women reported unequal treatment by healthcare staff

For instance, Stonewall found in their Unhealthy Attitudes report that same-sex partners have been excluded from medical consultations.

Sanjay, a health administrator in the east of England, reported to Stonewall that ‘Service users have reported not being allowed fertility treatment because of their sexuality. A lot of trans service users do not get the appropriate treatment from NHS services because of lack of knowledge, distance to travel to the nearest Gender Identity Clinic, and the fact that Cognitive Behavioural Therapy is recommended but is not appropriate.’

If you don’t have any experience in this area, you might be wondering what other specific issues lesbian, bi, and trans women face when accessing healthcare. The report covers some common concerns of LGBT people in the healthcare system.

Inappropriate Curiosity

According to Stonewall’s LGBT in Britain health report, one in four LGBT people reported inappropriate curiosity from healthcare staff because of their sexuality or gender, including half of trans people and one third of nonbinary people.

30 percent of lesbians and 23 percent of bi women face inappropriate curiosity, higher numbers than both gay and bi men.

It’s one thing to ask someone about their sexuality in order to treat them as best as possible. For instance, if a nurse asks about a woman’s sexual activity, knowing she has sex with women and not men is an important piece of information to have in assessing treatment.

Inappropriate curiosity would be forcing the woman in question to expand on her sex life, asking invasive questions about how she has sex, or making insinuations about what her sex life entails.

Discriminatory or negative remarks by healthcare staff

23 percent of survey respondents witnessed discriminatory remarks from healthcare professionals. In the past year alone, 6 percent of respondents including 20 percent of trans respondents heard these remarks.

In Unhealthy Attitudes, the Stonewall report asking healthcare professionals their experiences in the workplace with inequalities in treatment of staff and patients because of sexuality and gender identity, there are a large variety of discriminatory quotes. Some of them are second-hand from a witness, but others were directly told to Stonewall by these healthcare providers.

‘I have heard negative comments, referring to individuals as ‘it’ or ‘she males’, also comments about the appearances of trans people,’ says Fiona, a social worker from North West.

Emma, a support worker from the east of England, reported ‘I have heard colleagues telling others to make sure they always wear gloves as s a gay service user probably has AIDs.’

Donald, a doctor from the South East, spoke this way about LGBT patients. ‘The needs of others that are not the norm in my opinion should not be forced upon others that choose to be what we have up to now considered mainstream ‘normal’. As human beings, we are biologically programmed to function in a certain manner and deviations are not to be considered mainstream society.’

Lack of understanding specific LGBT needs

In Stonewall’s health report, 25 percent of LGBT people said they’ve experienced a lack of understanding of LGBT needs in healthcare. 9 percent encountered this in the last year alone. 62 percent of trans people have experienced this lack of understanding, 41 percent in the last year.

These problems worsen when sexuality or gender intersects with ethnicity and disability, with Stonewall finding that one third of disabled, black, Asian, or other ethnic minority respondents reported a lack of understanding of their needs.

Healthcare issues predominate in the LGBT community are depression and anxiety, along with suicidal thoughts, all of which are highly exacerbated for victims of hate crime-related violence.

In the past, women who have sex with women have been told they don’t need screening for cervical cancer even though this false.

Stonewall reports that 69 percent of LGBT people who experience a hate crime based on their sexuality or gender identity have a higher rate of depression.

The National LGBT Health Education Centre in the US also found in their 2016 study Understanding the Health Needs of LGBT People that there are higher risks of HIV transmission and smoking and substance abuse.

This report also found that LGBT women have much lower rates of receiving mammograms and pap smears than heterosexual women. In the past, women who have sex with women have been told they don’t need screening for cervical cancer even though this is false.

Lesbians and bi women also experience a lack of understanding of their needs at higher rates than gay and bi men, with 34 percent of lesbians and 21 percent of bi women as compared to 19 percent of gay men and 15 percent of bi men.

There is also always the risk of medical professionals blaming sexuality for health problems.

‘It was told my health conditions and issues were all caused by the fact I’m bi, even though I’m monogamously married and have dealt with the symptoms since I was eleven,’ says Imogen, 33, from Wales.

Outed without their consent

According to Stonewall, 10 percent of LGBT people and 27 percent of trans people have been outed by a healthcare professional without their consent. 15 percent of disabled LGBT individuals have been outed.

Being outed, for anyone who doesn’t understand the term, is when someone who knows your sexuality or gender identity informs someone else of this without you consenting to the other person knowing that information.

Laura Russell, Stonewall’s head of policy, says ‘There are certain particularly marginalized groups of LGBT people that are unable to be out with all of their friends, family, or in the workplace. If someone makes the call to say that you’re LGBT without your consent, that could put you at risk and sometimes a potential risk of violence if people find out.’

Kim, a youth worker from London reported in Unhealthy Attitudes that she ‘had a volunteer worker who was a lesbian. She was outed by another member of staff to a group of young people who attacked her on the way home.’

LGBT people can, like this volunteer, be outed to strangers or other healthcare professionals and put in danger that way. However, they could also be outed to homophobic or transphobic family members or employers who could create an ongoing issue of discrimination.

Are not out

9 percent of LGBT respondents in the LGBT in Britain survey said that they were not out to anyone about their sexual orientation when seeking general medical treatment. This affects both bi men and bi women more than gay men and lesbians; 29 percent of bi women are not out compared to only 11 percent of lesbians.

This can be an issue whether you’re not out generally, or just not out within the context of your GP.

‘Health professionals ask if I might be pregnant, and when I say no, follow up with ‘Have you had unprotected sex with your partner since your last period’ which, even if I had, would hardly get me pregnant. Having to decide whether to come out to people you hardly know and may never see again is never-ending and a little bit wearying,’ says Claire, 36, from Scotland.

I have my own experience regarding not being out to medical professionals. I’m from an extremely small, rural town in America. As a teenager, I saw a therapist for my anxiety and was extremely reticent to inform her of my sexuality. I kept it hidden because I was worried that she, like other people in my life, would not take my mental health issues seriously and instead blame my sexuality for any problems I had.

Avoided treatment for fear of discrimination

14 percent of LGBT people said that they avoided medical treatment entirely out of fear of discrimination, including 37 percent of trans people and 32 percent of non-binary people.

One in five disabled, black, Asian, or other LGBT people in an ethnic minority have avoided treatment, and one in four LGBT people between the ages of 18-24 have avoided treatment.

‘I’m worried my healthcare provider will not take my gender identity seriously,’ says Isra, 22, from Wales.

According to a transgender patient cited within the National Women’s Law Centre report, ‘Finding doctors that will treat, will prescribe, and will even look at you like a human being rather than a thing has been problematic. [I have] been denied care by doctors and major hospitals so much that I now use only urgent care physician assistants, and I never reveal my gender history.’

It’s unlikely that someone would just experience one of these forms of discrimination or unequal treatment, as many of them intersect. This makes it even harder for LGBT people to feel safe in the healthcare system.

While trans people are certainly the demographic most likely to experience these issues, lesbians and bi women are usually more likely to experience them than gay and bi men, with some exceptions.

When you combine homophobia and transphobia with sexism, problems in the healthcare system become more evident. When medicine is based on the experiences of cisgender men and heterosexuality, it’s non-heterosexual women and trans people who have less access to resources.

Mental health and sexual health

Mental health is one of the areas that affects LGBT patients most. 52 percent of LGBT people reported depression in the past year. This raises to 55 percent for LGBT women. 61 percent of LGBT people reported anxiety, with 65 percent for LGBT women. Both rates are higher than for GBT men. 67 percent of trans people reported depression, and 71 percent reported anxiety.

Bi women experience anxiety at the highest amount, at 72 percent.

This is much higher than general numbers of those who experience depression and anxiety in the UK, which is one in six people.

‘Doctors and nurses are really uninformed,’ says Lisa, 21, from Wales. ‘Going for an appointment about my mental health usually ends with me in tears because they’ve decided all of my anxiety and depression is caused by me being trans.’

The National LGBT survey found that accessing mental health care is more difficult for LGBT individuals than accessing general or sexual healthcare.

28 percent of respondents who had accessed or tried to access mental health services in the past year said it hadn’t been easy at all, either due to long wait times or a lack of support from their GP. While most reported positive or neutral experiences once they’d accessed care, 22 percent said they’d had a negative experience, some of them citing verbal harassment or bullying.

However, even though sexual health was found to be easier to access, lesbians and bi women had more difficulties in accessing sexual healthcare than gay or bi men.

There are solutions out there

None of these issues are impossible to solve, far from it. There are many things large and small that can be done to improve healthcare for the LGBT community.

‘Fundamentally, both individuals and institutions can take action to make sure that they’re providing inclusive support,’ says Laura Russell of Stonewall. ‘There are general things you can do in your daily life, if you’re making assumptions, and questioning the assumptions you do make.’

Other things someone can do in their daily life is asking questions and being open-minded to new information. Also, don’t get defensive if you’re corrected or told that you’re doing something wrong. Correct yourself and move on. Educate yourself.

Using inclusive language is also important, and it’s more than just not using homophobic slurs. Refer to a ‘partner’ or ‘spouse’ instead of a husband or wife, and don’t assume heterosexuality as the default. All of these are applicable in healthcare, but they’re equally important to just practice no matter who you are.

A huge key to change in the future is the ability to call others out for their homophobia and transphobia. Stonewall’s Unhealthy Attitudes reports that one in six patient-facing staff would not feel comfortable challenging their colleagues or their patients from making homophobic remarks.

60 percent of healthcare professionals who hear remarks like these don’t report them. Reporting harmful behaviours is the only way to get them to stop in the long run.

‘Both individuals and institutions can take action to make sure they’re providing inclusive support,’ says Laura Russell. ‘There are general things you can do in your daily life, if you’re making assumptions, and questioning the assumptions you do make.’

Laura Russell also has suggestions for medical institutions to take action in combatting homophobia and transphobia.

‘Institutions can take lots of actions to make their services more friendly,’ she says. ‘Whether that’s hanging posters for specific LGBT support services or taking part in a program like the LGBT Foundation’s Pride in Practice, there are lots of things that healthcare providers can do.’

Pride and Practice works alongside medical organizations to help provide the best care possible for LGBT patients, giving health institutions the resources needed to treat their LGBT patients equally.

Within their health report, Stonewall has a wide variety of specific suggestions for improvements institutions can make as well.

They suggest that NHS England should run highly visible national campaign against homophobia, biphobia, and transphobia where they encourage reporting these problems, along with instituting a Sexual Orientation Monitoring Information Standard and work on creating the equivalent for gender identity.

A Sexual Orientation Monitoring Information Standard is a system that would record sexual orientations, including heterosexuality, in a person’s medical file. Implementing this would allow there to be more accountability for medical professionals in making sure LGBT patients receive equal treatment. It also would allow professionals to more accurately assess health risks that predominately affect the LGBT community.

Organisations that provide training to future medical professionals need to review their curriculum, standards, and training to ensure that teaching covers homophobic, biphobic, and transphobic language and discrimination, along with information about the health inequalities for LGBT people and how to provide LGBT inclusive care.

Stonewall also recommends that healthcare providers need to prominently display zero-tolerance harassment and anti-bullying policies that encourage reporting issues, along with implementing mandatory diversity training that’s trans-inclusive.

Laura Russell also suggests joining Stonewall’s program for employers, the Diversity Champions Programme.

‘The Diversity Champions programme supports LGBT inclusive employers, and if you’re supporting your workforce, there might be things that people can take away that they can take into their own service delivery,’ says Russell.

There are other specialist services you can access that might serve your needs better than a GP.

Russell says, ‘There are some great services that provide specialist services like cliniQ, which is a sexual health clinic targeted specifically at trans people and does a lot to make trans people feel more welcomed.’

cliniQ is in London, but there a variety of specialist services available in different regions and targeted at different populations as well.

On their website, Stonewall has a What’s in My Area? directory that can tell you nearby LGBT resources for health and wellbeing, advice groups, and community groups.

Finding community

There are also less traditional sources you can go to for health resources. While nothing can replace going to the doctor, the Internet has made it much easier for specific questions LGBT people can ask about their needs that the people in their circles may not understand.

The Internet isn’t a replacement for real healthcare, but it can help answer questions about things like mental health and sexual health as an LGBT person in a safe, anonymous space. It also allows you to share your own experiences with those who may not have anywhere else to reach out.

Growing up, there was no one in my small town I could talk about my sexuality with. Even those who I knew wouldn’t treat me badly wouldn’t be able to understand the problems I had and how alone I felt without a community.

I only knew a handful of out gay people in my high school, and almost none of them were women. What helped me through my teenage years was being able to interact with other LGBT people online and share my experiences with others who had similar lives and problems to me.

Outside online communities, there are organizations like Stonewall that you can turn to for information, and websites like the LGBT Foundation that have a large number of potential resources.

Many LGBT organizations will prioritize gay men over women and trans people needing resources, and while gay and bi men are certainly a group affected by these problems, it can often be more difficult to find resources specifically for women. The LGBT Foundation has a ton of resources just for women, however.

The LGBT Foundation has a Confidence Movement for lesbian and bisexual women to help combat mental health programs. They even have a vlog series about women’s coming out experiences.

They have sexual health guides on their website specifically aimed at lesbian and bisexual women and why they need to be tested for cervical cancer and get mammograms regularly. They also have a guide to safe drinking and other advice directly from other LGBT women.

Information on safer sex is almost always aimed at heterosexual couples, and more often at gay and bi men than for gay and bi women. Most LGBT women will have probably dealt with invasive questions about lesbian sex at some point in their lives.

LGBT Foundation offers guides on sexual health for women on their website

The sexual health page for women on the LGBT foundation website has videos and guides about safer sex, masturbation, and a lot more.

They also offer free monthly workshops for lesbian and bi women in Manchester, along with offering resources for trans and non-binary people to reach out to health resources, change your name, and guides to sexual health.

There’s also a large community of lesbian and bisexual YouTubers who make content specifically for LGBT women.

The YouTube channel Rose and Rosie Vlogs feature a British married couple, Rose Ellen Dix and Rosie Spaughton, and many of their videos feature frank discussions of mental health issues in an inclusive way that’s specific to LGBT women.

Their video Talking about mental health: OCD | Anxiety | Therapy does a great job of highlighting mental health issues they both face in their real life in a way that’s applicable for their vastly lesbian and bi women audience.

Stevie Boebi, another YouTuber, has a series of videos specifically about lesbian sex, answering questions that young LGBT women may not know and won’t be taught by anyone else.

Getting resources from YouTubers, podcasters and other people in the media can feel more personal and less daunting than specifically seeking out LGBT organizational resources, especially for young women and women who aren’t yet out. It’s also accessible from all over the world, so you can find something regardless of where you live.

Even social media can help – connecting to other LGBT people across the world who have experienced similar issues in their lives can certainly help when it comes to mental health and sharing of resources.

Healthcare is moving in the right direction when it comes to LGBT inclusion, with laws like the Equality Act of 2010 prohibiting the exclusion of LGBT people from accessing healthcare and with inclusive training gaining more traction.

However, barriers remain in understanding and empathy. When institutions fell flat, LGBT people stepped in and created resources for their community. While these resources can’t replace equal, non-discriminatory treatment in healthcare or any other area of life, they are a reminder that LGBT people aren’t alone and can find help in one another.

More Healthista content:

Depressed? Anxious? These 10 nutrients are proven to help

This is what a vulva looks like

9 things I learned from sitting in a cancer ward for four weeks

This is what it’s like to go through gender re-assignment

‘I have Sjogren’s Syndrome – I didn’t know what it was either’

WIN an overnight spa stay worth £279 by taking our 5-minute survey

Do you want to experience ultimate relaxation? To be in with a chance to win an overnight spa stay for two including treatments and meals, complete our five minute survey about how your gut health affects your relationships

Like this article? Sign up to our newsletter to get more articles like this delivered straight to your inbox.